The ten principles of guitar design, Part 10, As Little Design as Possible

This is Part 10 of a 10 part series, applying Dieter Rams’ “10 Principles” to guitar design. Just as we did in previous instalments, we should understand that these principles were just one designer’s opinion as to how to evaluate their work, and that they’re presented in their original order assuming that there is no particular importance to that order.

Principle #10:

Good design is as little design as possible

“Less, but better because it concentrates on the essential aspects, and the products are not burdened with non-essentials.

Back to purity, back to simplicity.”

Erwin Braun said that their firm’s appliances “should be humble servants, to be seen and heard as little as possible . . . like a valet in the old days.” If we’re to apply this principle to guitar design, we would consider instruments to be tools that not only allow the performer to achieve their desired results, but do so without distracting the audience or impeding the performance. We’ve discussed this before with some of the other principles.

If you look at examples of Rams’ work, it’s easy to see where he was going with this principle. The shapes, forms, controls, and layouts are as simple as possible. The color schemes are minimal. Theres an absence of purely decorative features. You get the sense that it was better to execute fewer design elements well rather than more design elements poorly.

Rams still had to work within the constraints of production and the underlying technologies as they were absolutely necessary for the product to function as intended. As guitar designers, we face a similar set of challenges, but with the added responsibility of designing for “tone”.

Essential vs. Non-Essential

In order for us to determine what is and isn’t essential, we first have to answer the question: “What is a guitar?” We’d need to know the characteristics of the guitar before we could make assessments of individual design elements and the how essential they are to the Concept. You’d think this would be an easy task, as everybody seems to know what a guitar is, but a precise definition is elusive. Dictionary editors seem to have the same difficulty, as a quick survey of online definitions come up with the following characteristics:

Held against the front of the body, on the knee or suspended from a strap

Usually six strings

Plucked with the fingers or by plectrum/pick

Stringed Instrument – a type of Chordophone related to the Lyre

Long fretted neck

Flat-Backed

Rounded body that narrows in the middle

Flat sounding board with a hole in the center

Range of up three octaves or more from the E below the bass staff

The bottom line is that its difficult to pin down exactly what it is that defines a guitar, and therefore its hard to determine what is and isnt absolutely necessary when it comes to evaluating design elements in a concept just from a dictionary definition. We need to augment the definition by evaluating it in context, with the most obvious context being the personal preferences of the designer. If I, the designer, think that a particular design element is essential, then as far as Im concerned it is. Others may not share my personal preferences and may deem that particular element as non-essential, or worse. Using my preferences as the context may help me satisfy my own personal requirements regarding this principle, but it thats where it ends.

What is the absolute minimum required then, if youre evaluating somebody else’s design concept and the elements of that concept? How would you determine what things were necessary and what things were extraneous? Again, personal preference would play a part, but you could also attempt to understand the design choices in terms of the overall concept of the guitar. In other words, is a particular element required by the concept, or could it achieve the designer’s goals without it?

Just for drill, let’s take a couple exception examples above and evaluate the necessity of some design elements in the context of how theyre being used. For T-Bone Walker, it’s clear he needs an instrument that is small enough to facilitate his playing position, and we could also say that it must be of a type and appearance to suit the gig. For the Ovation acoustic, the concept is centered around the material and shape of the bowl back itself, making the design element absolutely essential to the design. Does it need to have the traditional Ovation headstock and the pickup system? It depends on what you believe the concept to be, and for many players both elements are essential to what they expect from Ovation.

The exception examples also clearly show that we have a lot of latitude as designers. Our designs dont absolutely have to have 6 strings, frets, flat tops, binding, rosettes, dovetail neck joints, etc. if it doesnt fit our concept. In fact, for some concepts, these design elements would be completely unnecessary, and adding them would constitute a violation of this principle.

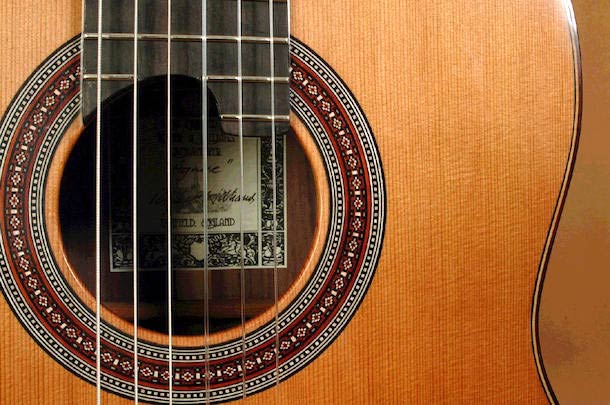

Market pressures play a part in determining what is practically necessary, if not absolutely necessary. If youre designing for a particular brand and they have a design element that is a signature of that brand, then its probably going to be required to include it. Headstock designs are a good example, as you can often recognize the manufacturer from just a silhouette of the headstock. Classical rosettes are another, and to some extent binding an inlay as well. All of these design elements can be considered as functionally essential as they all serve a purpose, but its also true that they can include details that may be considered non-essential and purely decorative, therefore violating the principle.

Different concepts are going to come with different expectations. For years, the expectation for fine acoustic guitars is that they have backs and sides made from rosewoods, mahogany, or maple and tops made of one of the spruces. If a manufacturer wanted to a model to sell to a market that held that expectation, then they had better use traditional woods in their design. This expectation has relaxed quite a bit over the years, but it is still evident in some market niches.

Availability and cost play into the selection and specification of particular material or component part of a guitar design because of constraints. In a perfect world, no species of wood or model of part is absolutely required for a particular design unless its a key element of the concept. As a practical matter, though, you may be required to use something because of a constraint, such as availability, cost, time, etc. The same can also be said of tooling and machinery constraints, as some design elements might be required due to the tooling and skill sets available for manufacturing it.

The Tyranny of Strings

The only absolutely essential design element of a guitar is that it has strings, anchored and pulled to tension, and with that comes the requirement that your design will include straight lines. Unlike other consumer products, its impossible to design a guitar using nothing but curves. To some extent, this plays in our favor as straight lines are easily machinable using traditional hand and 2D oriented power tools. Even with this imposition of straight lines, you can still impart visual motion as evidenced by this ergonomic bass design below. You could even argue that the twisting of the fingerboard is an essential design element since the guitars Concept is ergonomic.

It is possible to design, build, and play a stringed instrument that has a fixed tuning. By “fixed”, I mean that once the string is pulled into tension and anchored, theres no method for the player to change the tension on the strings. That is, short of using heat and or humidity to change the dimensions of the framework holding the strings and their anchors. As a practical requirement then, a guitar design must have some mechanism for adjusting the tension on the strings and therefore the pitch the string vibrates at.

For guitars and basses, this usually means we have tuning machines attached to a headstock, but obviously that isn’t an absolute requirement with the availability of “headless” tuner designs. The designer is free to choose the particular type of mechanism, but as a practical matter they have to choose something, and it should fit the rest of the concept. Other practical requirements include that they be easily adjustable, ideally mid-performance, dont foul or interfere with the other tuners, doesn’t create balance problems, are reliable, operate smoothly, and fit easily in cases or bags.

Guitars are classified as chordophones, and a chordophone is any musical instrument that makes sound by way of a vibrating string or strings stretched between two points, with or without a resonator. This implies that we incorporate two specific design elements in our concepts. The first is that the strings are anchored on both ends, and the second is that the string vibrates between two fulcrums. If we stuck a couple screw eyes in a board, then attached and tightened a wire between them, then the screw eyes would serve as both anchors and fulcrums.

On most guitars, the tuners serve as anchors on one end, with a bridge or tailpiece serving as the anchor on the other end. With headless designs, the ends are switched. The nut and saddle perform the fulcrum duties on most guitars. Some concepts will also require some form of compensation at the bridge saddle and possibly at the nut as well. While all guitars require anchors for the strings, they dont necessarily have to be elaborate as the EDS-1275 below shows. Some are similarly simple, running through the guitar body reinforced with string ferrules.

As a string vibrates, it needs additional room for clearance, otherwise it will create a buzz as it contacts the frets or fretboard. Larger gauge strings tend to need more room, and this is why guitars are typically setup with a higher action on the bass strings than on the treble.

You could make a straight fretboard that has zero buzz by raising the action, usually by raising the saddle height. Another approach is to allow the string tension to pull the neck into a slight curve, creating “relief” along the fretboard. This allows the player to use notes lower on the fretboard with reduced buzz while still having a manageable string height or action higher on the fretboard. It is common for classical guitars to have a slight relief planed into the fretboard, however most steel string acoustics, electrics, and basses use a truss rod adjustment to dial in the desired amount of relief. While it’s not absolutely necessary to have an adjustable truss rod, most players have come to expect them in instruments other than classical guitars. As a practical matter, relief of some sort is a necessary element of a guitars design.

A typical set of strings for a six string acoustic guitar tuned to standard tuning can exert a pull of between 120 and 210 pounds. A twelve string electric bass can pull almost 420 lbs. This tension will create several issues that need to be addressed in the design of the guitar, such as:

- Deformation of the neck and fingerboard

- Pull and Torquing of the string anchors

- Deformation of the body, the top in particular

- Downforce on the bridge saddles and nut

- Reaction to shock, e.g. falling off a stand

Depending on the concept of the guitar design, dealing with this force is either trivial or not, and critical or not. For a solidbody electric guitar, it’s mostly a matter of choosing a body material that can hold on to a fastener and not get crushed by downforce on the saddles, and installing an adjustable truss rod. For acoustic guitars, its a much more complex combination of materials and layout, adhesives, and reinforcement while still allowing the top to move. Designing for both tone and durability is much more difficult for acoustic guitars, and tradeoffs can be made depending on the concept. For example, I could trade off some useful lifetime of the guitar for what I might think is a better tone. An analogy might be designing a car for racing rather than for hauling groceries.

Finally, some thought should be given to String Fouling, making sure theyre free to operate as intended along the entire string path. This is usually an easy requirement to meet and the typical string path layouts between the anchors and fulcrums satisfy the need, but its still an essential design issue that should be addressed.

The Human Interface

As players, weve come to expect that guitars will be designed so that theyre comfortable to play, allow us to focus on the performance, and otherwise make us feel good. Design features that accomplish these goals are a practical necessity, and for some players it’s an absolute necessity. While a T-Style electric made from a slab of solid marble may or may not have great sonic characteristics, few of us would want to play a 4 hour bar gig with one strapped over our shoulders. For lap steels and resonators played horizontally, a rounded neck isnt required for comfort, and therefore would be an example of an unnecessary design element.

Balance is also a practical necessity given traditional playing positions. In some cases, a design element such as a body outline, profile, or combination of shape and material may negatively effect the instruments balance. You could then argue that the imbalance not only negatively effects the instruments playability but is also unnecessary and in violation of this principle.

Parametric control over volume, tone/EQ, pickup wiring, effects, etc. have to be considered in terms of their importance to the overall concept. For an acoustic instrument, these controls are not absolutely required, however from a practical perspective they very may well be. For electric guitars and for most electric guitar players, application of this simplicity principle may be more appropriate than not. More than one electric guitar has been designed with switching options that rarely if ever get used.

Guitars have a functional lifetime over which we expect that their use will impart some wear and tear on the instrument. A particular design element, such as the choice of neck/body join, may bring with it consequences as it relates to durability and repairability. It is not necessarily an absolute requirement that a design element allow for easy repairs or replacement (e.g. standard sizes for through-peghead tuners), but as a practical matter its unnecessary to include design elements that prevent future repairs.

The Short Answer…

To score high on this principle, every element has to be evaluated as to whether or not it’s essential to the concept. Whats essential for one concept, player, marketplace, or intended use may not be essential for others. While Rams’ might have deemed unnecessary the application of Eddie Van Halen’s Frankenstrat stripes to an electric razor, another designer working on an EVH product might require them.

Sticking to essential elements and simplification of design can, but not always, result in lower cost, easier/faster/cheaper production, better maintainability, and possibly better performance. It’s not always an easy process, though, especially for designers that are working on their first few designs. I think all of us have gone through a phase where we abandoned simplicity in a quest to design the “ultimate” guitar. As we continue our work, we often find that simpler designs that stick to the essentials have a better chance of success.