The ten principles of guitar design, Part 8, Details

This is Part 8 of a 10 part series, applying Dieter Rams’ “10 Principles” to guitar design. Just as we did in previous installments, we should understand that these principles were just one designer’s opinion as to how to evaluate their work, and that they’re presented in their original order assuming that there is no particular importance to that order.

Principle #8:

Good design is thorough down to the last detail

“Nothing must be arbitrary or left to chance. Care and accuracy in the design process show respect towards the user.”

I assume that since Dieter uses the word “nothing”, he must mean that he’s not only addressing aesthetic design elements, but also functionality. I’m guessing he might extend this principle through to the engineering of the actual product. This is another Principle that guitar designers and builders compromise on a regular basis, sometimes out necessity but possibly more often out of simple laziness. I’ll be the first to plead guilty to this charge, though, as I’ve left some design details to be finalized later during the fabrication process. There have been times when my failure to think through all the details in the design stage have left me with something that just didn’t look 100% right as it left the bench.

The Wisdom of Planning

Failing to Plan means planning to fail, and an incomplete plan is better than none. I don’t know who came up with those quotes originally, but in my experience they’re spot on. This shouldn’t come as a surprise to anybody who has designed and built a few guitars, as the process of Design itself is a form of planning. If you haven’t thought through all the details, how they fit together with other elements, and how you’re going to fabricate it, then you haven’t finished your plan and therefore haven’t finished your design work.

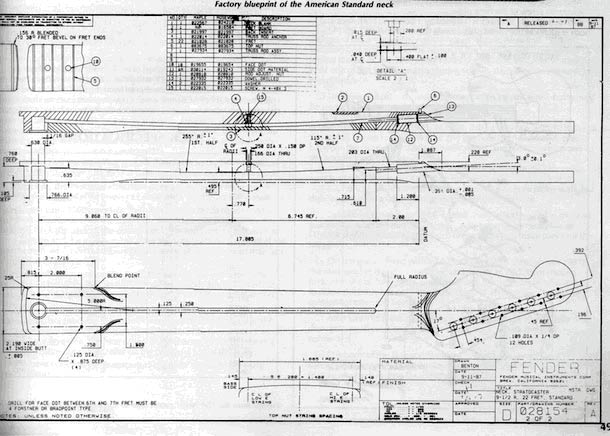

Detailed planning is absolutely required for mass production, including something that looks like a Bill Of Materials and Production Routings. A manufacturer has to know what it’s going to cost to produce parts, what they need to source, and a plan to maintain consistency. A good plan can have a positive effect on efficiency in production, and help ensure things are fabricated in a way that you had intended them to.

Planning for Art, Craft, and Custom building is a bit more forgiving. For example, it maybe enough to know what kind of screws will be used, but not necessarily what type of head or their exact locations since the designer is often the builder, too. In other cases, it might be critical to know that information and detail it in the plan. Sometimes it’s just better to avoid “Paralysis by Analysis” and get on with the work. For custom luthiers, there will be times when a plan doesn’t survive contact with the realities of the build, and they’ll have to adapt, improvise, and overcome to move the build forward.

To adhere to this Principle, the guitar designer must take responsibility for every detail of the Design. This includes the materials used, the parts sourced or fabricated, the integration of all the design elements, sequence of operations in production, adaptability throughout the instrument’s life cycle, and it’s transport. There are designers that prefer to leave details to the builders after they’ve come up with the Concept and perhaps a nice sketch. Dieter might say that they’ve purposely scored low on this particular Principle.

The Boeing 777 has been described as “Three million parts flying in close formation.” As incredibly complex as the design for a commercial jetliner is, it’s critical that every part works smoothly with everything else. Given the expense of fuel and the demands for efficiency, there’s little room on board for any component that literally doesn’t pull it’s weight. Everything has to serve a functional purpose, and it has to look like it belongs as well.

Guitars are not as complex as jet airliners. I would suggest, though, that it wouldn’t hurt to use the 777 example when thinking through your design work, evaluating how everything fits and functions together, and figuring out what is simply dead weight.

Details That Fit the Concept

In a good guitar design, everything fits together both physically and aesthetically. Every design element looks like it belongs and integrates well with the other elements. It doesn’t mean that the details themselves need to be complicated. This is another Principle that meshes well with the “Appeal to Simplicity” as it makes the work much easier to integrate the design details within a cohesive Concept if it’s straightforward.

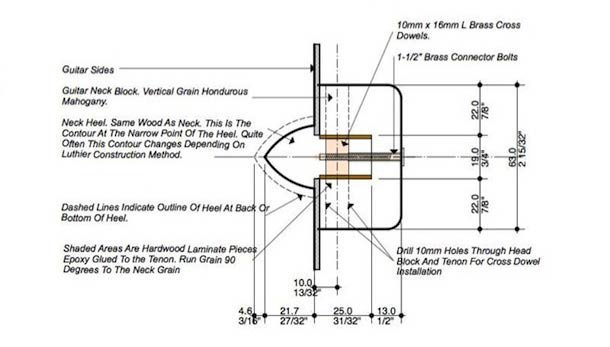

It’s important to consider the functional details as well as the aesthetic details in the plans. Every design element has to co-exist with other design elements. For example, cavities and controls must be accommodated in areas that don’t weaken or expose other design elements. The classic example is in the neck join area where the presence of a pickup route can weaken the join if it’s not properly planned. Another is a roundover of the back that would intersect the planned control cavity or cover. A detailed plan would help prevent such an unfortunate situation. Details such as dimensions, centerlines, center points, and construction notes are much easier to do in a drawing application, but can also be handled with pencil and paper.

I can’t think of a single guitar design I’ve done that was 100% on it’s first pass. None of them survived entirely intact through the build, either. At least this Principle gives you an opportunity and reminds you to check all the details, evaluate them, then make adjustments in subsequent iterations of the design.

Nothing should look to be “tacked on”, out of place or added as an afterthought. Every detail should fit within the overall Concept. Consider the Fender Cabronita example below. You may argue that the guitar should have a pickguard as it serves a functional purpose, namely protecting the face of the guitar, even if it’s on a pre-relic’ed instrument. It’s not covering any control or pickup cavities, wiring channels, or other functional duties, but at least it follows the outline of the body. Others might say that it looks like it’s there just because somebody thought that it’s ancestral lineage dictates that it must have a pickguard, so put something on there even if it’s not otherwise required. Does it really need to protect the horn, or are they doing that just because it’s that way on their other instruments?

Reality Presents Important Details, Too

All consumer products are meant to be used, but musical instrument design presents additional challenges in meeting the objective and subjective criteria of the user. Guitars are by their very nature “high-touch” experiences and also engage multiple senses when in use. Everything must built for performance as well as appearance, and there are numerous design elements that can be critical to the success of an instrument’s performance. Examples of such elements are fret end treatments, upper fretboard access, balance, fingerboard radius, control layouts, weight, and tuning stability. These details can also be dependent on the genre of music and respective player preferences, too.

There are also the minor details of money and availability. Both have to be considered when planning and evaluating the detail specifications in the plans. If you specify a part and it’s simply not available at a reasonable price that keeps the instrument within a budget constraint, then you’re going to have to specify something else. Then you’ll have to think through any potential interactions it has with other parts and design elements, and also have to evaluate how it fits in with the overall Concept’s aesthetics.

I like to think that a guitar that gets used is a happy guitar. Like anything else that gets used, it’s going to require some kind of service or repair at some point. Some are mundane, such as string changes, compensation adjustments, tremolo spring tension adjustments, truss rod adjustments, an so on. A good designer is going to think about these things and make sure that they can be easily done. All of us have seen a Stratocaster that has had its tremolo cover removed from it’s back, done so because it makes string changing easier. Just as you wouldn’t enjoy changing spark plugs on a car that requires the engine to be removed first, you’d prefer that all adjustments can be made without taking the guitar apart. It wouldn’t kill us to think of how to make things easier for a repair person in the future.

Guitars typically need to be transportable, and some thought should be given to how the player is going to get it from point A to point B in one piece. Custom cases are always an option, at least as long as time and money aren’t a problem for you. Otherwise, designing to fit an existing case type is an important detail, and frankly one that gets missed a lot. Another one that is getting increasingly more important is planning for the instruments demise, making sure that everything can be recycled or disposed of when it’s useful life is over.

2 thoughts on “The ten principles of guitar design, Part 8, Details”