The ten principles of guitar design, Part 4, Understandable

This is Part 4 of a 10 part series, applying Dieter Rams’ “10 Principles” to guitar design. Just as we did in previous installments, we should understand that these principles were just one designer’s opinion as to how to evaluate their work, and that they’re presented in their original order assuming that there is no particular importance to that order.

Principle #4:

Good design makes a product understandable

“It clarifies the product’s structure. Better still, it can make the product talk. At best, it is self-explanatory.”

Definition of “Understandable”

Of course, we want our player to understand our guitar designs so that they can effectively use them. We need to determine if the guitar’s design is “to be expected, natural, reasonable, or forgivable.” Hopefully little or none of the latter, but there will be times when a Constraint forces you to do what you can with what you have to work with. You could present the guitar to any player that has a reasonable idea as to what a guitar is and they would be able to perform with it. That would extend to other stringed instruments similar to guitars, such as the electric ukelele: anybody that had a basic knowledge of electric guitars and ukeleles could pickup and perform on this instrument. They’d either assume that the control knob is there to adjust the output or volume of the instrument, or they’d figure it out very quickly.

You could argue that if a person didn’t know how to tune a ukelele much less play it, they wouldn’t find the example presented to be intuitive at all. Couldn’t you say the same thing about practically any other kind of consumer product, such as a toaster, can opener, or kitchen appliance? We can assume a reasonable expectation that our players will have at least a fundamental and basic knowledge of what a guitar is and how they are used. Most guitar players should be expected to have an understanding of our ukelele example, even if they don’t play the Uke. Just as we’d expect an experienced pilot of a business jet would understand a modern, “intuitive” cockpit design, we’d expect our players to understand an instrument geared towards their level of expertise.

One assumption we make of guitarists that we don’t make of other stringed instrument players is the need for positional aids built into the fingerboard. A traditional violin, viola, cello, or double bass does not have any dots on the side of the fingerboard or “fret markers” on the top. The player is expected to learn exactly where they need to put their fingers so that the notes play in tune. Guitarists are not held to this same standard, and most will reject a guitar that doesn’t at least have markers on the top edge of the fingerboard. Not having the dots makes the guitar less understandable than one that does.

What is Reasonably Understandable?

Some designs are going to require some explanation, even if they appear to be very simple. One growing area of innovation in guitars is Modeling, which is the use of sophisticated computation and synthesis to produce the sounds of many different types of instruments from one physical instrument. For the most part, current examples look and play much like any other guitar, but the player has the ability to select tonalities of other instruments. For example, they could play the modeling guitar and have it sound like they’re playing a banjo, sitar, jazz hollowbody, or whatever.

We’d expect that the player would require some minimum amount of education on exactly how to operate the Modeling system. A good design would be one that a player could figure out from a simple description, short video, or controls showing them everything they’d need to know in a matter of seconds, like a knob with the instruments labeled around it. A less successful design would be one where the player would have to enter in cryptic UNIX terminal commands presented on a 16 character LCD display. The terminal approach may be much, much more powerful, but the learning curve would be very steep.

Some instruments may destined for international markets where the players may not speak the language that the manufacturers do. Or the products may be typically used in environments that are not well lit, foggy, or otherwise extremely dynamic in nature, much like your typical stage. A player will develop some muscle memory and reach for the right knob or other control instinctively, just as a pilot in a cockpit would, but there are still times when they’re going to have to look at what they’re doing. In the world of consumer electronics, it’s common to find devices that have little or no verbiage on their control surfaces, opting to use iconography instead. We see that from time to time in musical instruments and accessories as well, exemplified by this amplifier from Orange:

Appeal of Simplicity

In general, the simpler an instrument is, the more intuitive and playable the instrument will be. It will also have fewer things that could possibly fail during performance, which can be a significant factor in how the player evaluates and bonds with the guitar. However, simplicity may impose limits on what can be done with it and restrict the instruments versatility. Not every player needs the Swiss Army Knife of guitars, but they also may need more than a One Trick Pony. What they really want is a whole bunch of One Trick Ponies and their own personal guitar tech’s, but practicality and limited money usually drives them towards guitars that provide a range of useful sounds that fit common musical situations.

Sometimes designers are tempted to do things simply because they can. With electric guitars based on traditional magnetic pickup technology, it’s hard for some to resist the urge to provide as many possible electronic controls and combinations. None of these are particularly difficult concepts for guitarists to work with, but in practice many of the options can be rarely used. If the controls aren’t labeled, it’s easy to forget which switch does what. Take for example the two electric guitars below. If you were seeing these for the first time and had no other prior knowledge about their operation, would you know what each switch and knob does? Would you remember their layout and functions later when you’re in the middle of an extended jam?

Changing the Interface

Consumer products constantly get more technology and functionality stuffed within the confines of their form factors, such as phones and other mobile devices. We’re seeing the addition of more technology into guitar designs, such as the Modeling technologies mentioned earlier. Other examples are the Robot and MaGICS systems from Gibson, as well as midi touch controllers like the Kaoss Pad.

With phones and other mobile devices, changing the interface from a knob and button based form to a soft, programmable touch screen opened up new possibilities and capabilities. They’ve turned a simple mobile phone into truly Personal Computers. We may expect the same thing to happen with guitars. Instead of volume and tone knobs, phase and coil cut switches, and other traditional controls, we should expect to see them be replaced with soft programmable touchscreen interfaces, at least for new designs. Their capabilities could be enhanced to control not only the guitar’s variables, but also those in the pedal board, amp, PA, lights, and other devices.

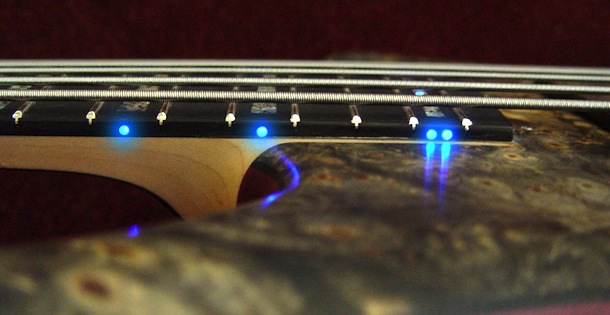

We’re also beginning to see technologies implemented in guitars for the purposes of pedagogy, with the intent of making them easier to learn how to play. One example is the Fretlight system, a guitar with lights embedded in the fretboard and controlled by a system that shows the player where to put their fingers. You could say that this is a technology that makes the guitar more understandable. Another training tool in development is the gTar, powered by an iPhone which synthesizes the sounds as well as lighting up the fret positions. The computing and communications capabilities of a smartphone, along with the soft programmable touchscreen interface, open up opportunities for enhanced control and understandability.