The ten principles of guitar design, Part 2, Usefulness

This is Part 2 of a 10 part series, applying Dieter Rams’ “10 Principles” to guitar design. Just as we did in Part 1 (Innovation), we should understand that these principles were just one designer’s opinion as to how to evaluate their work, and that they’re presented in their original order assuming that there is no particular importance to that order.

Principle #2:

Good design makes a product useful

“A product is bought to be used. It has to satisfy certain criteria, not only functional, but also psychological and aesthetic. Good design emphasizes the usefulness of a product whilst disregarding anything that could possibly detract from it.”

Definition of “Useful”

Naturally, when I look up the dictionary definition of the word “useful”, it presents a circular reference involving the word “use” which itself is defined as “employ”. To be “useful” means that something can be used for a practical purpose, or “of a practical or productive kind.” Substituting words leads us to a definition where we’re employing a tool to accomplish a task, like applying a wrench to a nut or bolt. The emphasis is on the practical, getting a job done.

In the context of guitar design, then, what do we consider the word “useful” to mean? What is the job to be done? Is the design geared towards musical purposes, or is it intended to do something else like allowing ugly guys to attract beautiful girls? It depends on what your idea of a practical purpose is at any given time. For our discussion, though, I think we’ll focus on the former rather than the latter as we as designers have more control over the outcome.

We should also consider whether or not the design can be applied to a wide variety of possible uses or targeted to accomplish a specific function. One design may have more utility than another for a particular player, genre, or venue, or be suited for practically any environment that it finds itself in. In other words, a particular guitar may be useful and valuable because of its sonic flexibility, and another guitar may be useful and valuable because it has a very limited capability set but performs those specific functions extremely well.

We could limit our boundaries and simplify, asking ourselves if the design in question makes sounds that musicians can apply to their work. Or, we could expand our scope and ask ourselves if the overall Concept and design can be used to accomplish a practical purpose that may or may not involve sound. My guess is that almost all of us are focused on making music, but that doesn’t mean that the latter isn’t a valid Concept or isn’t useful.

Functional

Let’s consider a guitar design’s capabilities and utility in producing musical sounds. The first question we’ll need to answer is: “Is it playable as a guitar?” Can a guitarist equipped with reasonably sufficient ability be able to employ the design and create music with it? Admittedly I’m setting the bar very low, but I’ve left it open to encompass designs that have either real or virtual strings and can be operated in a manner similar to a traditional guitar. Others may not be so generous in setting their baseline for functionality.

If it is playable, we can then evaluate whether or not the design make it easier or harder to play. Here we’re focused on the intended use of the instrument, the player and genre, etc. An instrument with a 10 foot scale and a neck as big as a fencepost may make musical sounds, but it may not be very easy to play. This is an exaggerated example, but more than one instrument that looks good on paper has proven itself to be difficult to play.

We want to evaluate a guitar’s performance as well as its appearance on the stand or hanging on the wall. If it has controls of whatever kind, can they be intuitively recognized adjusted during a performance? Can adjustments be made quickly and easily, and are the range of adjustment parameters within useful and functional boundaries?

How about the day to day requirements of playing the guitar? Can I get strings for it? How about a case? Accessories? If a design calls for strings with an unusual scale length, material, anchors/ends, etc., then a limitation in the availability of those items means a limitation in the functionality of the instrument. Custom cases are expensive, and some designs require large cases that are less practical than standard sizes as well as expensive, and these considerations can also be considered as limitations on functionality.

Is the design ergonomic? It should be reasonably comfortable to perform with. Many players need instruments that can accommodate their own physiques, so any design that doesn’t would be deemed dysfunctional.

Does the design include features that solve problems for musicians? Is the tool right for the job, and does it address their needs as a performer? If it doesn’t do what a player needs it to, then it doesn’t matter what it looks like.

Psychological and Aesthetic

Let’s assume that a particular guitar design meets our criteria for functionality. Under a very strict definition of usefulness, that would be enough to qualify. What would make it more useful is if the design creates a bond with the player in such a way as it enhances their performance and image while using it. A guitar that doesn’t fight the player is one that allows them to focus less on the mechanics of playing and more on the expression.

Just because a guitar is functional doesn’t mean that it balances well, is comfortable, or feels good to play. A design that comes up short in any of these areas may be deemed dysfunctional. Preferences are going to vary from player to player, as some prefer a thicker neck profile than others, some can live with neck dive while others can’t, and some players can’t get through a 4 hour gig with a heavy guitar.

A guitar’s appearance is also an element of its utility. Does the design fit the intended purpose, player and genre? Would it look out of place at a blues jam, coffeehouse gig, jazz club, metal show, etc.? A great player can probably use anything in any venue and make it work for them, but most players are going to gravitate towards something that is not only functional for the type of music they play but also has an appearance to match.

Let’s consider some solidbody electric guitar examples:

Hello Kitty Strat: Originally targeted at pre-adolescent girls, these have become sought after by male players specifically because they look out of place in male-dominated genres of metal. From a functional standpoint, they are straightforward and simple designs that can work well for heavy music. From an aesthetic standpoint, they look completely wrong juxtaposed against songs about death and violence, which is the intended effect the player has in mind. They’d also work both as an instrument and as a prop for your typical pop princess.

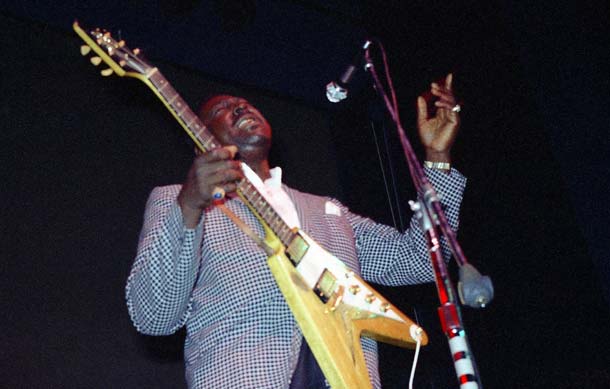

Flying V: The three “Modernistic” designs created by Gibson in 1957 were not dramatically different from their predecessors in terms of functionality. Their aesthetic features, however, were an attempt to use then-contemporary aerospace themes as a way to gain back some market share from Fender. If tailfins worked for cars, then it was thought they could work for guitars. The “plank” body featuring mostly flat surfaces instead of carved arches were obviously gaining acceptance, and far easier to manufacture. While these designs initially flopped in the marketplace, they eventually morphed into icons of rockstar imagery, although now they’re found in a variety of genres and venues.

Countless pointy guitars: These typically have functionality that is well-suited for hair metal, thrash, death metal, and other forms of aggressive music, equipped with locking tremolos, high output pickups, perhaps a kill switch, etc. Aesthetically, they harken back to a simpler time filled with battle-axes, maces, and other sharp pieces of weaponry. They’re also often adorned with graphics to match, and you may wonder what kind of rounds they fire. These aesthetic design elements enhance the functionality of the guitars because they convey an image the performer wants to project. When you want to level a city with rock, an ES-175 probably isn’t going to do it for you. Conversely, not many players are going to bring a BC Rich Mockingbird to a jazz trio gig.

There are times when a designer will be faced with a series of decisions regarding whether or not to preserve traditional design elements or abandon them. Ned Steinberger opted to eliminate headstocks from his designs because they were functionally unnecessary, and subsequently many players deemed a headless guitar to be too ugly for them. Some even attached fake headstocks to make them look “right”.

Floyd Rose produced the Discovery series of guitars that featured a double-ball end string technology but opted to include a headstock for aesthetic reasons even though it served no functional purpose. A Concept based on a Strat with a double locking tremolo wouldn’t look right without something that at least resembles a Fender headstock.

The Benedetto “Benny” is functionally a simple solid body guitar, but included a number of aesthetic design elements that echo those of their traditional jazz guitars and would look completely at home in a jazz venue.

Emphasis on Usefulness

If we accept this principle, then we should evaluate a design’s success by asking ourselves how well the guitar performs in its intended use. When they think of the guitar, a player will judge it based on its ability to produce sound and execute the player’s will. T

hey would get the impression that the designer made their choices with utility in mind above appearance or artistic expression.

Sometimes it appears that designers don’t hold to this principle. A classic example is the Gibson Moderne, where the outline of the headstock takes precedence over the functional benefit of a straight string path from nut slot to tuning head. To make it functional, the designers had to employ posts to guide the string which can’t possibly improve tuning.

Other designs are clearly meant to be more works of art than instrument, even if they’re playable. Some seem to function as merely platforms on which to execute decorative arts, like a canvas for a painter. With extreme examples, it’s almost like displaying the Mona Lisa in a bus station bathroom; its function is to decorate and be viewed, but using it would certainly risk getting damaged. Who would want to be the first to subject a work of art to a case of buckle rash, pick scratches, smoke, and Budweiser?