Fundamentals of Electric Guitar Design Pt. 4 Putting Theory into Practice: A Rework

After three installments full of nomenclature and theory, I thought it was time to show how these ideas can be used to discover and solve design problems. Here’s a rework I did a few years ago, of a guitar that I actually own and like, the Schecter Avenger. I remember seeing it in the store and digging its lines, and it had a neck and fretboard on it that I really liked. I happened across one on eBay in perfect shape, with a factory case, for 300 bucks and couldn’t resist.

I didn’t know at the time that this model was originally a Teisco model, called the Spectrum 5. It debuted circa 1966, with 5 ‘half-pickups’ covering three strings each. It had a deep ‘German Carve’ on the body, a pickguard, and six rainbow-colored sliding switches, one for each PU and one ‘Mono’. It also had a 4×2 headstock with a big angular bulb. There had been earlier Spectrums, with different, more Stratlike bodies. Then there was at least one more version after the 5, with two rectangular single-coils. (see pic)

I’d had a Schecter Saturn since 1985, and it had served me well. The Avenger sounded pretty good, though I eventually replaced the Asian pickups. It’s a killer mahogany Metal guitar now.

At any rate, I’d been designing guitars for a bit and sat one day, analyzing its lines, and trying to understand why it nagged at me a bit. (One thing I didn’t like was that the top horn will dig you in the left nipple sitting down, God help you if you have a ring in yours.) So I took a flat picture of it, traced and scanned it into my drawing program and started measuring and overlaying axis lines.

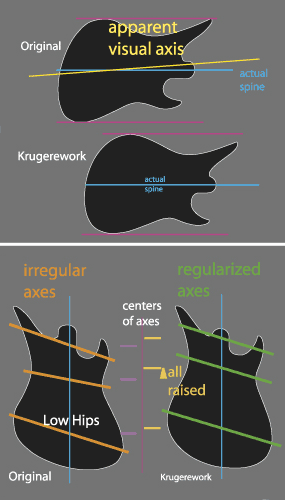

I openly state that the tracing is not dead perfect, as I was redoing it anyway. But it was close enough, so why spend hours tweaking. The first thing that jumped out at me was the fact that the center line of the body wasn’t really in line with the neck’s, it runs uphill in the playing position. That disparity is never a good thing.

Whether it was rotated sometime in the building process in order to solve a balance issue, or was simply not finely analyzed, there it was, and the more I looked at it, the worse it stood out. To make matters worse both the horns point left, (or up) and tend to lead the eye off the main Spine axis as well.

The next revelation came when I drew its Thrust Axes across the widest and narrowest points. They weren’t really consistent with each other, and pointed out how ‘low’ its hips were. While this model is what I call an Avid type (leaning forward), having its Waistline more upright tends to stifle that forward flow to some degree. Having a headstock that leads down also fights the overall impression.

Its headstock really had little in common with the body, other than being asymmetric, so I knew I’d better sort out the body first and then adjust a new head to match. Which is the better order, usually.

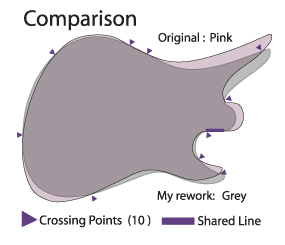

So I had a fairly nice, swoopy body with a broken back, and a too-long torso. How to fix it? Well, the final result you see here is actually the Sixth Version I did, I’ve spent more time on this guitar than just about any of the 210 I’ve done… but I just had to make it work, after a while it became an obsession. Sure, there was no real reason other than intellectual curiosity, but I had time to kill in those days. Of course, if I could show the Schecter folks how I’d improved their product one day, well, that might get me a foot in a door.

First priority was to rotate the body and redraw it so it didn’t look quite so bent. Then I decided I had to ‘pull it pants up’, and raised the widest points of the big end by a couple inches. Unfortunately this tended to point up the ‘scooped’ nature of its flanks, so I was forced to round those out a bit more, like an acoustic’s. This then forced the waist and shoulder lines forward some, as well.

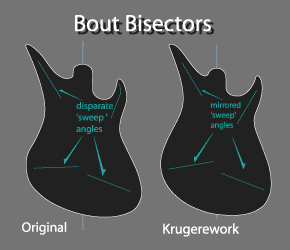

Rotating the body had helped to make it look less ‘off’, but by drawing the guitar’s Bout Bisectors, it helped to see how different its interior, ‘assumed’ angles were. The absolute hardest part, though, was getting the top line of the guitar to reconcile with the rest of the piece. The lower horn wasn’t too far from a Strat’s, a model I’d picked apart many times over in the past. But turning one out, and one in, is tricky!

Since the Hip Line axis is biggest, and wasn’t unpleasing, I repeated that angle at the waist and shoulders, and set the lower horn where it needed to be, relative to the top of the fretboard. That gave me all the ‘bones’ I needed to make it all come together. I had the Spine, and two of three Axes, and a bisector line for the lower Horn bout. Over the course of a few sessions, I found the ‘right’ place for the waist, judging between where the top and bottom of the guitar had to turn, for both to appear comfortable. Flipping the Bisector of the lower horn helped some, but it still needed sliding back and forth along the Spine to figure where that evil top line had to turn, in order to make the top horn end up in the right spot. I’d keep thinking I had it right, and then try spinning the guitar around to see it from all angles, only to discover how lumpy and misshapen I had it. Ovals are the most difficult shapes to draw… circles can be done mechanically.

Eventually it came together, through the course of a thousand little adjustments. If you look at the Comparison, you will see that the two designs, though close, and related, share almost no line and crisscross many times. But finally I’m satisfied that I have a new, better version, that few could find fault with.

Millions of people over thirty years had seen no problem with this guitar, but there are some of us who do. If you are cursed with that sort of insane focus, well, you’re in the right place I guess. Consider this group therapy. Send me 300 dollars immediately.

So now I had a full-sized body and neck, and had to do something with the headstock. At the time I’d only seen the Schecter’s. So a six-in-line seemed the thing to do, given that a double-cutaway is usually seen with that configuration. But, as all the lines in this new prettier body swooped forward and up, it seemed a ‘reverse’ headstock fit the bill most appropriately.

I took some of the repeating forward-leaning body lines and set a few out at the head end as loose guide lines and set to work. I knew I didn’t want it to have a strictly straight back like the original, as there are no other straight rules on the whole body. So I gave it a soft long arc, with a small flick at the tip. The ‘burning can opener’ aspect came from looking at the two horns, they just looked like licking tongues of flame. (I am generally reticent to have a pointy tip on headstocks, but felt the design motif fulfilled here could justify it, this time. ) In truth, it almost drew itself, in one of those Eureka moments where you do something and realize its ‘rightness’ later.

Once that motif appeared, I echoed it into some custom fret-markers… I was rather shocked to realize after forty years or so of looking I’d never seen those anywhere – you’d think someone would have done them at some point. (and they may have, I admit I haven’t seen everything).

Once done, I named the new model The Flicker, as that’s what fire does, and, if set in the right typeface, it could read as something slightly more… attention-getting. I have sculpted this model at full size, and it’s both comfy and functional… as well as being kind of a badass to look at. The women who have seen it always seem to remark on it.

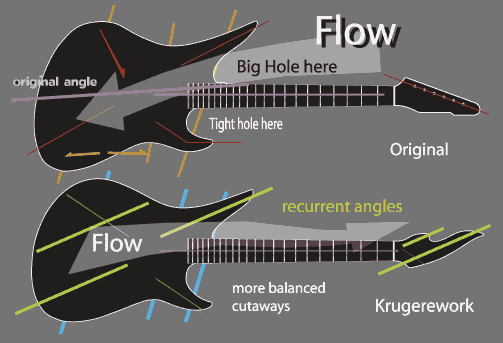

In telling my tale I’ve glossed over an important design concept, that of a guitar’s Flow, an ephemeral idea, felt as much as seen. It’s hard to judge, and many guitars don’t have much… especially Static thrust types. Many times its non-presence or confused nature is easier to appreciate. Think of it as its Chi, or internal energy… it has a path. In the original Avenger, the combination of the divergent main Axes, the larger top cutaway, and the visually ‘spreading’ Controls Bout seemed to suck the spirit of the guitar backwards and down… two directions that seemed to fight the overall forward Thrust intended.

Part of the problem is the much larger hole left by the top cutaway… while the horn leads the Eye off the body, the Brain tends to want to investigate holes, we’re curious creatures, and in nature, caves, crevasses, niches, etc, can contain things we need to know about, whether they be dangerous or advantageous. Is there a mountain lion in there, or a quart of honey? I call this Crevice Curiosity, and the picture attached demonstrates it beautifully. It’s something to remember, that both phenomena are going on simultaneously, and you can consciously steer them to your benefit.

I think my version has successfully solved that Flow issue, and brought the model into its own, finally made whole. Let me know what you think. Those of you with operating guitar companies who might be interested in licensing this design should feel free to contact me! I’d love to see it made.

Next time, I’ll share a few secrets every sign painter knew in the Seventies that can make you a better guitar designer! Kerry Kruger, Miami.